CDH stands for Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia and is called medfødt diafragmahernie in Norwegian, or medfødt mellomgulvsbrokk

CDH occurs due to an incomplete closure of the diaphragm in the unborn child, usually around the 8th week of pregnancy. The hole allows organs from the abdomen, such as the spleen, liver, stomach and intestines, to move up to into the chest cavity and prevent the lungs from developing normally. The condition can occur on the left side, the right side, or a lot less common on both sides.

How is CDH diagnosed?

Usually, CDH is discovered before the child is born, during an early or routine ultrasound appointment between week 15 and 22 of pregnancy. For the midwife, doctor or gynecologist, the indication is often that it is difficult to see the diaphragm, that the stomach lies next to the heart, and that the heart is displaced to the right or left, depending on which side the hernia is on. The smaller the fetus, the more difficult it is to detect. Only when the fetus has passed 20 weeks is it possible to say anything about the size and outcome of the hernia, and thus the prognosis. Diagnosis before week 13 is rarely possible.

Only hospitals with a fetal medicine department can diagnose CDH. At other hospitals or private ultrasound clinics, a referral is needed to confirm CDH. Although several hospitals have fetal medicine departments and neonatal intensive care units, as of today only Rikshospitalet in Oslo and St. Olavs in Trondheim have the expertise to receive and treat children with CDH in Norway. There are approx. 6 children born at Rikshospitalet and 1-2 children at St. Olav’s annually (figures from 2022). After a confirmed diagnosis, you will be connected to one of these two hospitals for further follow-up. In the most serious cases with a need for FETO intervention, the hospital refers further abroad, usually to UZ Leuven in Belgium.

First meeting with the hospital

Thanks to increasing knowledge about the diagnosis, the prognosis for most children is promising. But since most of the examinations take place later in pregnancy, the diagnosis is often presented with general information rather than individual facts when expecting parents first meet with the doctors. The hospital is obliged to provide parents with this information so that they can make an informed choice about whether or not they wish to continue the pregnancy. Many unfortunately experience a lot of focus on the potentially worst degree of severity, and that they are encouraged to terminate the pregnancy. However, the general experience is that when the couple eventually decides to continue the pregnancy, the doctors’ focus also changes, and they are met with a more forward-looking attitude and a follow-up plan.

Prognosis and tough decisions

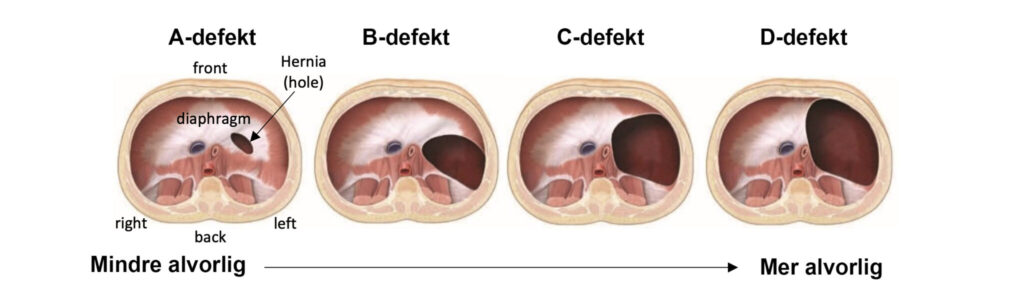

Today, 1 in 2.500 children are born with CDH in Norway. CDH often occurs in isolated and spontaneous cases, but in 40-50% of cases the diagnosis is part of a larger spectrum of birth defects or syndromes (source). In order to map any other health challenges, the hospital encourages you to take a NIPT test (non-invasive) and a possible amniocentesis (invasive). If there are no other findings, the prognosis is good for the child in the vast majority of cases. The survival statistics in Norway are around 90%. In order to be able to say more about the child’s prognosis, the fetus must be large enough for an ultrasound examination to be able to confirm which organs are located in the chest cavity. Soft organs such as the stomach and intestines take up less space and thus do less damage to lung tissue and the heart than heavier organs such as the spleen and liver. The fetus is usually large enough for this examination around week 21. It is important to emphasize that the organs can move later in the pregnancy and thus this examination is not a final confirmation of the size of the hernia. Organs can also move up and down between each ultrasound examination.

If it turns out that CDH is part of a larger disease picture in the child, the prognosis will depend on the challenges these other diagnoses bring. A few syndromes associated with CDH are not compatible with life, but the vast majority are. It is a big and inhumane task to have to decide whether it is a life you want to bring into the world. There are many considerations to take into account with such a decision. Ending a pregnancy is not an easy decision for anyone, and this choice must always be respected. It is nevertheless important for us as an organization to show that there is hope for these children and that CDH in isolated cases is not necessarily a death sentence. We emphasize this so that when the choice is made, it is based on a nuanced picture of the diagnosis and not solely on the dark image painted by the hospitals.

LRH, lung hypoplasia and pulmonary hypertension

Around week 22, a so-called LHR (lung head ratio) will be measured. It measures the amount of lung tissue, but it cannot say anything about the function of the lungs. Most times only one lung can be measured, as the lung located on the same side as the hernia will be enveloped in other organs and therefore not possible to see. The LHR should be 1.0 or higher for the child to have sufficient lung tissue to be considered compatible with life. Fetal diagnosis has its limitations. Although LHR measures lung volume and this is used to interpret the amount of lung tissue, it is challenging to assess the degree of hypoplasia (number of alveoli and effective gas exchange). All children with CDH also have pulmonary hypertension (source) (an elevated pulmonary arterial pressure), but the pressure cannot be measured until after birth and thus it is not possible to say whether this is at a critical level or not. It is therefore limited what a prenatal medical examination can predict about the child’s prognosis. The two latter conditions are unfortunately the ones that create the greatest challenges for the newborn child’s chances of survival. It is therefore important to understand that even if the lung has a promising LHR number, the lung’s function may still be very limited. Having said that, neonatal medicine has taken a quantum leap in the last 20-30 years, and both knowledge, surgery, medicines and life-saving machines (such as the NAVA ventilator, oscillator and ECMO) mean that even the sickest patients have an increased chance of survival – and many do survive.

The fetus’s prognosis (before birth) is based on 3 main criteria:

- If the fetus has other additional diagnoses that worsen the prognosis

- The fetus’s LHR (lung to head ratio) measured between weeks 22 and 28 gives a 64.5% accuracy in forecasting (source).

- Whether the fetus’s liver is below or above the diaphragm

The liver can also be partially over, in which case an approx. percentage of how much liver is in the chest cavity. The liver is an important indicator as it is large and considered a solid organ, and will therefore limit the lungs’ growth opportunities significantly more than other softer organs.

You will probably hear or read people talking about a certain percent chance of survival. This is more common abroad, but has also occurred in Norway. Rikshospitalet does not operate with percentages, but St. Olav’s occasionally do. Usually you are given a prognosis in the form of a mild, moderate or severe case.

Which syndromes/diagnoses are associated with CDH?

- Trisomy 13

- Trisomy 18

- Down syndrome 21

- Turner syndrome

- Trisomy 5p

- Tetrasomy 12p (Pallister-Killian syndrome)

- Fry’s syndrome

- Simpson Golabi Behmel syndrome

- Cornelia de Lange syndrome (NIPBL gene mutation)

- Pentalogy of Cantrell (POC)

- Marfan syndrome

- Beckwith-Weidermann syndrome

- Goldenhar syndrome

- Pierre Robin sequence

- Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome (RTS)

- Several types of heart defects (CHD / congenital heart defect)

(Source)

Ultrasound or fetal MRI?

In Norway, ultrasound is used in the examination of fetuses with CDH. A fetal MRI is not usually part of the routine procedures, as it is in the USA, among other places. The reason being that in most cases it is considered both an expensive and unnecessary examination, with increased risk for both mother and child. Norwegian doctors agree that the benefits of the information a fetal MRI can provide are so few that the use of resources cannot be justified. However, exceptions are made where necessary. In the USA, the examination is often used to measure the size of the hernia, as well as the total volume of the lungs. Among other things, LLSIR (lung to liver signal intensity ratio) is measured, which has been shown to be related to lung maturation.

Waiting grief

The time from the diagnosis until more information is available can be experienced as long and frightening. On top of this, dealing with the fact that a lot will be uncertain until after birth is a heavy psychological burden. Many feel overwhelmed, at a loss and in a state of anxious waiting. As a pregnant woman, you will be informed that with such a serious diagnosis, you can choose to terminate the pregnancy up to week 22. For many, it is difficult to deal with such a choice. The combination of a short deadline and a feeling of not knowing enough about their child’s prognosis puts parents in an inhumanly difficult position.

The way forward after the diagnosis

If you choose to continue the pregnancy, follow-up checks and further examinations will take place at the fetal medicine department at the hospital you are connected to. The frequency of the checks depends on where in the country you live and when in the pregnancy the diagnosis is discovered. On average, you will be asked to come in for a check every 2-3 weeks at the start and once a month later in pregnancy, if everything seems to remain stable. Some doctors will say that it is rare for more organs to move up into the chest after the 21st week of pregnancy, but for some patients it still happens if the hernia is large enough. Since the hernia cannot be measured by ultrasound, this is not possible to predict. The hernia is still the same size throughout and will not grow or shrink during pregnancy. The defect already occurs during the formation of the diaphragm in week 8 of pregnancy, and remains the same until birth and surgical repair. Some will have more frequent checks if, for example, the fetus shows signs of growth abnormalities or has an additional heart defect (CHD). You will receive a tailored follow-up plan adapted to your child.

Delivery and hernia repair

The vast majority of children with CDH in Norway are delivered by planned caesarean section at week 38. However it is not considered dangerous for the child to be born vaginally, and in some cases initiation is planned rather than a caesarean section. For this, there are slightly different protocols at Rikshospitalet and St. Olavs. However a known CDH case will never be allowed to go all the way to term and be born spontaneously, unless it happens before the planned birth. This is solely due to the hospital’s need for planning and organizing, so that the team that will both receive the child and care for it afterwards are rested and alert. It also makes it possible to plan the birth so that the child arrives on a weekday with full staffing and not on a weekend or holiday. If you live far away from the hospital, you will probably be registered at the patient hotel from week 36 or 37, to make sure you are nearby of the birth starts earlier than planned. It is important to emphasize that it is you as a woman giving birth who has the final say in how you want to give birth. It is your body, even if it is not always presented this way by the doctors.

Regardless of the degree of severity, the child will immediately after birth be sedated, intubated (get a breathing tube down their throat) and be connected to a ventilator (breathing machine). Parents must therefore mentally prepare for not being able to see or hold their child, as with the birth of a healthy child. As soon as the child is stable, it will be transported to the pediatric intensive care unit (at OUS) or the neonatal intensive care unit (at St.Olav) where it will remain until it can be weaned off the breathing tube after the repair surgery and recovery time. In most cases, the child is operated on during the first week of life. Depending on the size of the hernia and the condition of the child, this is done with open surgery, or in some cases with peephole surgery (smaller defects). If the diaphragm muscles can be sewn together, this is done. For larger hernias, a synthetic patch of GoreTex is often needed. In cases where many organs have migrated into the chest, the circumference of the stomach will not be large enough to be closed after surgery. In these cases the child’s stomach will be closed step by step, and in the meantime a vacuum patch is used to replace the missing skin. The closure is usually done in 2-3 operations over a week’s time.

Hospital stay

Mothers and fathers/co-mothers of sick children are usually given priority for a private room in the maternity ward. After a caesarean section, you stay here for an average of 3-4 days, and after discharge you move into parents’ accommodation or a patient hotel at Rikshospitalet, or in your own room next to the child in NICU at St. Olavs. From 2031, there will also be private rooms in the intensive care unit at Rikshospitalet. The hospital is undergoing major rebuilding and renovation and the living conditions in the meantime are unfortunately far from optimal. After weaning from breathing support, the child is transferred to an intermediate post in the children’s surgery department if it still needs continuous supervision, and finally transferred to a newborn post or bed post in the children’s ward at the local hospital in your home town. At the local hospital, the focus is on going home. This means feeding therapy, weaning off medication and training parents in the use of equipment that may accompany the child home.

Follow-up

As a general rule, the child will be followed up at the university hospital for the first year of life, but further checks will be scheduled if necessary based on the child’s state of health. In most areas, check-ups with a paediatrician, and possibly a pulmonologist, nutritionist and physiotherapist, at the local hospital are sufficient. This depends somewhat on what resources are available in your city. Children with CDH are recommended to be vaccinated against RS virus in the first two years of life, influenza, and chicken pox after the age of one, before starting barnehage (daycare). Some patients only need following up in childhood, while others continue to be seen by doctors up well into adolescence and adulthood.

What subsequent challenges do children with CDH have?

CDH is a serious malformation with a wide range of severity, but many CDH children survive and live healthy and normal lives, with or without the need for aids and medicines. Which health challenges the children may need following up on and help with later in life depends to a large extent on any additional diagnoses and length of stay in hospital. It is therefore impossible to cover everything. Some challenges have nevertheless been shown to apply to a good number of children, for a shorter or longer period of their childhood, and for some throughout their lives:

- Eating refusal/food aversions

- Need for tube feeding

- Challenges with weight gain due to high metabolism

- GERD (Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease) (GØRS in Norwegian)

- Asthma

- Delayed fine motor development

- Delayed gross motor development

- Delayed cognitive/mental development

- PAH, secondary pulmonary arterial hypertension

- Chronic respiratory failure/lung disease

By the age of 3, most of the children will be at a normal level of development for their age, especially gross motor skills, and have a normal level of activity. Some may still not have caught up with their healthy peers when it comes to mental development (cognition), receptive language and fine motor skills. The delay can be compared to that in premature children (source). Length of hospital stay, need for oxygen supply for a long time and need for ECMO after birth are factors that influence the degree of delay in development.

Will we have more children with CDH?

In most cases, CDH is not hereditary and cannot be prevented either. The chance of having another child with CDH is very small, but since the cause of the diagnosis in most cases is unknown, the probability in isolated cases is still stated to be 2% per subsequent pregnancy, and 10% after having given birth to two children with CDH (source). Genetic screening is an option you can talk to your doctor about.